The anatomical

album from which the twelve drawings are taken contains

an autograph note on a loose sheet attached to the

pad, bearing the words: Anatomical and Artological

Drawings / produced in my early years, namely when

I was 15. 16. 17 years of age. And in winter alone./

Drawings of Bones are in Five Plates/ and Anatomical

Drawings number Thirty-eight. (The term "artological"

stands for "artrological", or relating

to the study of articulations, because some of the

plates addressed the main articulations in the human

body).

Vincenzo

Camuccini, a pupil of Corvi, was one of

the greatest exponents of Neo-Classical painting

in Rome, where he was born in 1771. In the early

years of the 19th century he was to become one of

the most authoritative painters not only in cultural

circles in Rome but in the art world in Italy as

a whole. From his early youth he took an interest

not only in painting but also in drawing, both from

a strictly educational point of view and in terms

of the production of sketches and models for his

paintings. He maintained a constant distance from

the pre-Romantic approach that was gaining a foothold

in Rome at the time, choosing instead to pursue

the path of Classicism; and then, not following

in the footsteps of Batoni but preferring a more

orthodox kind of Classicism that was more interested

in the systematic study of Classical antiquity and

of the Cinquecento.

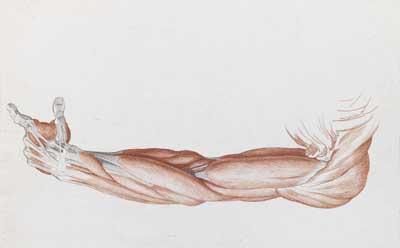

The twelve Anatomical

Drawings from Life published here are unquestionably

an important instance of the artist's very early

graphic work as well as offering an interesting

example of the history of anatomical drawing tout

court. The twelve sheets are part of an album containing

anatomical (osteological and myological) studies

of skinned bodies, preserved by the artist's heirs

after his death. As Paola Salvi has pointed out

(Salvi, 2001, p. 103), this corpus of drawings was

collected and collated in the album by Camuccini

himself, a suggestion confirmed in an inventory

dated 1824 and in the above-mentioned autograph

noted attached to the album. The volume, measuring

698 x 530 mm, is bound in full skin and the sheets

are applied to the centre of the right-hand pages

only; the spine bears the abbreviation: Disegni

D’Anatom presso il vero. [Anatom. Drawings

from Life].

An article by Hiesigner tells us that the plates

were produced in the artist's formative years between

1786 and 1788, when the artist was aged between

15 and 17, while he took an interest in the study

of Classical antiquity and the Old Masters between

the ages of 16 and 18. In this connection Hiesinger

writes:

After leaving Corvi’s studio, Camuccini resumed

an independent program of training under the supervision

of his older brother Pietro. It was at this time

that he began to find permanent direction through

a scrupulous study of antique sculpture and Old

Master paintings. By his own account, Camuccini

spent three years, from 1787 to 1789, studying the

Vatican frescoes of Michelangelo and Raphael. This

he supplemented by practice in drawing from life,

and between 1786 and 1788 by visiting the hospital

of S. Spirito to study anatomy from cadavers. (Hiesinger,

1978, p. 301)

As Hiesinger points out, in the later 1780s the

painter was wont to visit the hospital of Santo

Spirito in order to study anatomy from real corpses

(so to call them "from life" is perhaps

somewhat inappropriate) and thus to practise drawing

the human body. In academic terms, the drawing of

anatomy was considered a prerequisite for everything

else, a crucial stage in one's studies that preceded

any further artistic approach to the human figure;

indeed so much so that Camuccini's biographer Carlo

Falconieri, writing in 1875, stresses the point

that:

As Hiesinger points out, in the later 1780s the

painter was wont to visit the hospital of Santo

Spirito in order to study anatomy from real corpses

(so to call them "from life" is perhaps

somewhat inappropriate) and thus to practise drawing

the human body. In academic terms, the drawing of

anatomy was considered a prerequisite for everything

else, a crucial stage in one's studies that preceded

any further artistic approach to the human figure;

indeed so much so that Camuccini's biographer Carlo

Falconieri, writing in 1875, stresses the point

that:

[…] recognising that, without the study of

anatomy, there can be no skill in drawing for use

in the creation of works of art, [Camuccini] took

care to mete out his time to the second so that

he could devote several hours each day to going

to the hospital of Santo Spirito in order to draw

there the body prepared by the surgeon's knife;

without which training the painter and sculptor

would produce weak figures, like a building without

foundations. He first went to osteology, and thence

to myology, so as to discover not only the shape

of muscles but the reason underlying the movement,

action and rest of the muscles, tendons and the

more vivid display of veins. (Falconieri, 1875,

p. 18).

The importance of these sheets in the history of

anatomical drawing is pointed up by Salvi when she

states, in her study, that despite the fact that

the practice of the study of anatomy in the Neo-Classical

period is known primarily thanks to the series of

Antonio Canova and to Giuseppe Bossi's Corso miologico

[Course in Myology], Camuccini's work, by comparison

with that of Canova and Bossi, "is more obviously

designed for the study of movement, and offers a

more targeted identification of the changes that

occur in the modelling as the body assumes different

attitudes" (Salvi, p. 106). This approach produces

an extremely plastic depiction typically inspired

by the work of Michelangelo, as Mellini points out

in connection with the artist's later work (see

Mellini, 1998, pp. 500–505). Bossi's Corso

miologico adopts a more analytical criterion in

its execution, thus more in the style of Andreas

Vesalius and closer to the system of depiction regulating

drawing for more properly scientific purposes, thus

distant from any specifically artistic inclination.

In Camuccini's anatomical work, on the other hand,

it is immediately clear that the artist is interested

in the possibilities offered by movement, especially

in the later sheets where his research into the

different positions of his figure is characterised

by a strong plastic approach, often accentuated

by emphasising the poses and imbuing them with expressive

intentionality.

The drawings had originally been ordered in the

album by similarity of subject, regardless of when

they were drawn, but their chronology emerges fairly

clearly from the use of sanguines of different texture

(which can be distinguished by their colour) and

from the change in style, moving from less complex

to more complex compositions. The views of the hand

(fig. 2) seem to belong to a very early period,

whereas those of the foot and leg (fig. 7), while

still descriptive by comparison with the final sheets,

seem to betray a more marked desire to study movement.

It is only in the final drawings, however, that

the artist's purpose seems to be aimed more clearly

towards a syntaxis of movement and the potential

morphological changes that it causes. Starting with

the sheets showing the upper limb in various positions,

although always static (figs. 2–3), the artist

subsequently moves towards increasingly complex

poses, until he reaches the point of outright flexion

and contortion, as in figure 7 which, as Salvi points

out, echoes a similar study by Michelangelo for

the left arm of Night now in the British Museum

in London (see Salvi, p. 109). Lastly, figures 10

and 12 belong to the series of drawings devoted

to the trunk which, in terms of their execution,

are unquestionably the most complex and indeed also

the latest in chronological order. This last group

is the group that most closely echoes Michelangelo's

manner of depicting the human figure, a characteristic

that was to return with some frequency throughout

Camuccini's subsequent artistic career.